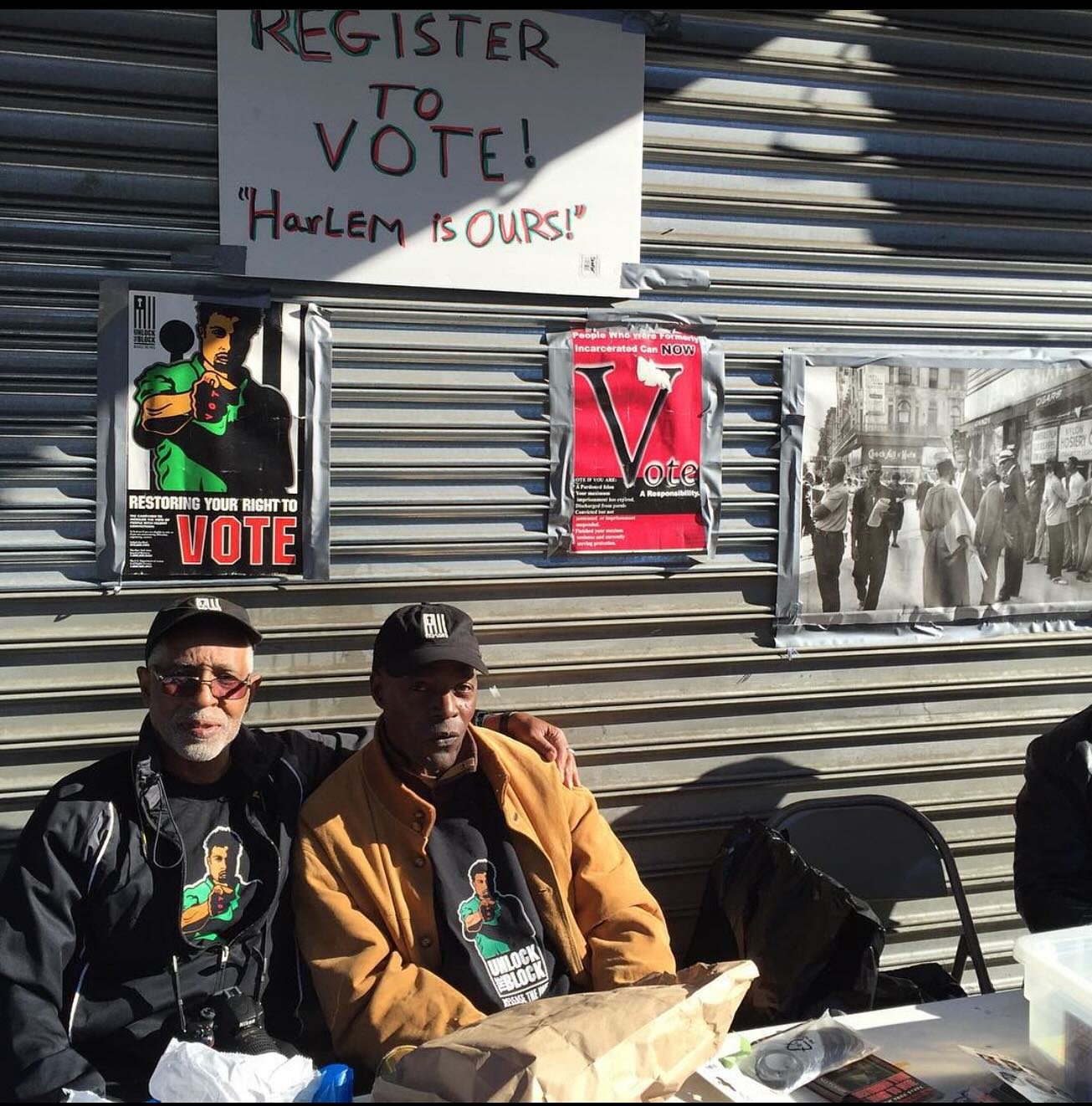

JOSEPH ‘JAZZ’ HAYDEN, HARLEM GANGSTER-ACTIVIST ICON, INSPIRED REFORM BIBLE ‘NEW JIM CROW’, IS DEAD

JOSEPH 'JAZZ' HAYDEN "MADE IT COOL FOR GANGSTERS TO BE ACTIVISTS."

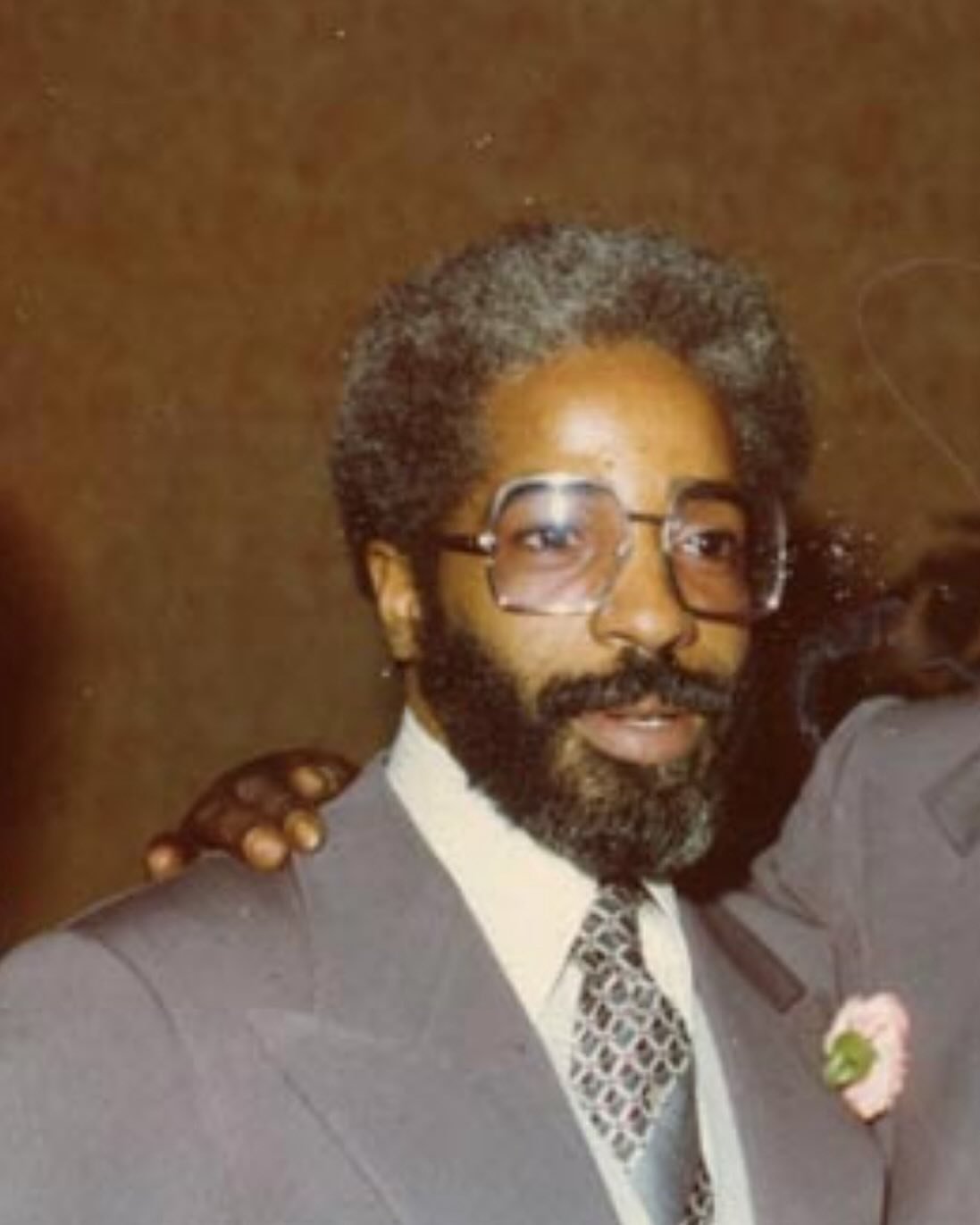

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden in the mid-1970s. Photo credit: via Facebook.

THE FREE LANCE NEEDS YOUR DONATIONS TO SURVIVE. DONATE HERE.

Legendary Harlem gangster-turned-criminal justice reform icon Joseph "Jazz" Hayden has died. He was 82.

Hayden started out as a small-time hustler, was wrongly convicted of attempting to assassinate two NYPD officers in a Black Panther hit in 1968, organized prisoners in advance of the 1971 Attica Rebellion, served on an infamous 7-member Black organized crime group called "The Council" then went on to become a celebrated civil rights activist who inspired others to become reformers like he had done.

While serving time for manslaughter in the 1990s, Hayden started what would turn into a national fight to restore the voting rights of former felons. When he was released, he co-founded and produced a criminal justice-focused radio program on WBAI called On the Count, pioneered "cop watching" to combat the NYPD's stop-and-frisk abuses and founded a local news blog, All Things Harlem.

Perhaps most significantly, but also least known, Hayden inspired Michelle Alexander's book The New Jim Crow—three confidantes of Hayden told The Free Lance.

The book and its criticism of America's "criminal legal system" is the bible of the current criminal justice reform movement.

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden (l) speaking at Riverside Church with Angela Davis (c), Michelle Alexander (2d from right) and (r) Cornell West on Sept. 12, 2012. Photo credit: screengrab All Things Harlem.

Hayden was born in Harlem Hospital, May 12, 1941. His parents soon separated and he more-or-less raised himself on the street.

"Jazz was a true son of Harlem. He embraced the streets, the music, the hustle, the Revolution, the struggle and the triumphs," said Jamal Joseph, a Black Panther veteran, Columbia University professor and close friend of Hayden's since 1974.

Joseph revealed Hayden earned his nearly lifelong nickname, "Jazz," when he was 11 or 12.

"He carried a trumpet around when he was a kid. He carried it around and played it," Joseph recalled. "The older cats named him that. He loved him some Jazz."

Hayden's uncle was a numbers runner who taught young Jazz the numbers game. Police caught the 16 year-old with 11 bags of heroin worth $2 each, earning him three years in state prison in 1957.

"The first night they locked me in a cell, I was rehabilitated," Hayden told journalist TJ English for his 2011 book about New York in the 1960s and 1970s, The Savage City. "I'd never been away from home, never been in this kind of situation, this cement and steel, I cried."

Prison made Hayden conscious of racism for the first time.

"Growing up in Harlem, I didn't know nothing about racism 'cause it was all black people," Hayden told English. "I could walk from 155th Street to 125th Street every Sunday to go to the movies, and every block I pass they wavin', and everybody dressed up and going to church."

But in prison in rural upstate New York, the "guards were all white, country boys; they had tobacco juice dripping down their shirts. Clubs big as baseball bats. They ran everything."

Harlem in 1955; Harlem nightclub, undated. Photo credit: NYC Municipal Archives.

Back home in Harlem in 1968, Hayden was falsely accused of attempted murder for allegedly shooting two NYPD officers. It happened the night after West Coast Black Panther leader Huey Newtown was sentenced to 2-to-15 years in prison for killing a police officer. A six-foot tall black man in a black cape with orange lining opened fire with a semi-automatic .30 caliber rifle on two cops sitting in a parked police car. The cops returned fire and, though wounded, survived.

Hayden, five-foot-six or so, knew about the Panthers, but said he avoided them because he was focused on chasing street cash.

"I stayed away from the Panthers because I had business to do," he told English.

Prosecutors dropped the original charges, but brought new ones alleging Hayden fired at police while fleeing from their unlawful attempt to arrest him for a crime he didn't commit. A jury convicted him and a judge sentenced him to 8 1/3-to-25 years. Hayden served a year-and-a-half before that charge, too, was finally dismissed after a successful appeal.

That year-and-a-half changed Hayden's life because he spent it at Attica.

Attica, Sept. 10, 1971. Photo credit: New York State Archive.

Between the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement, law enforcement authorities were locking up all kinds of non-traditional criminals motivated by politics.

"You had the Young Lords, you had the Weathermen, the Students for a Democratic Society, Black Panthers, Black Liberation Army and countless other groups," Hayden recalled in a 2011 interview. That "generation was not accepting the status quo. They were challenging it on many levels."

Many of the politically-motivated prisoners were well-educated.

"All of a sudden we got these guys running around with these educations," he explained. That made Attica "very different" from "any place I'd ever been before. It was almost collegial. Like a college campus or something."

"In the yard, we were having study groups," Hayden revealed. On weekends, they'd line up chairs "in a row on one side and teach law classes. Everybody needed law classes."

"We had turned that yard into Harvard. It was Columbia. It was NYU," he added. "These guys were scholars. They were intelligent. They had heart. They had principle. They had all of that."

"What we did in that yard, we eliminated all the differences that we had among us," he explained. "It was no longer my group and your group and this group and that group. It was us, and them."

Guards, for their part, were "literally sleeping, in the yard, while all this was building up around them."

Hayden was transferred out six days before his comrades revolted over inhumane treatment and living conditions, seized control of D-block yard, took several guards and civilian prison employees captive and issued demands for prison reform.

Gov. Nelson Rockefeller ordered police and guards to storm the prison on September 13. They unleashed an indiscriminate 4,500-round fusillade into the yard murdering 39 people—29 prisoners and 10 guards. After they regained control, guards and police tortured some survivors and summarily executed others.

No police officer, guard or official was ever held accountable for any crime.

Decades later, Hayden looked back and recognized that Government officials' murderous response "couldn't have been anything but what it was. This is how America conducts its foreign policy all over the world. You either obey, or we'll kill you."

After Attica, he said, his "politicization was complete."

US Army soldiers being briefed by Special Forces officers outside Attica before the Sept 13, 1971 massacre. Photo credit: New York State archive.

Lofty political ideals can't fill hungry bellies. Nor can they pay rent.

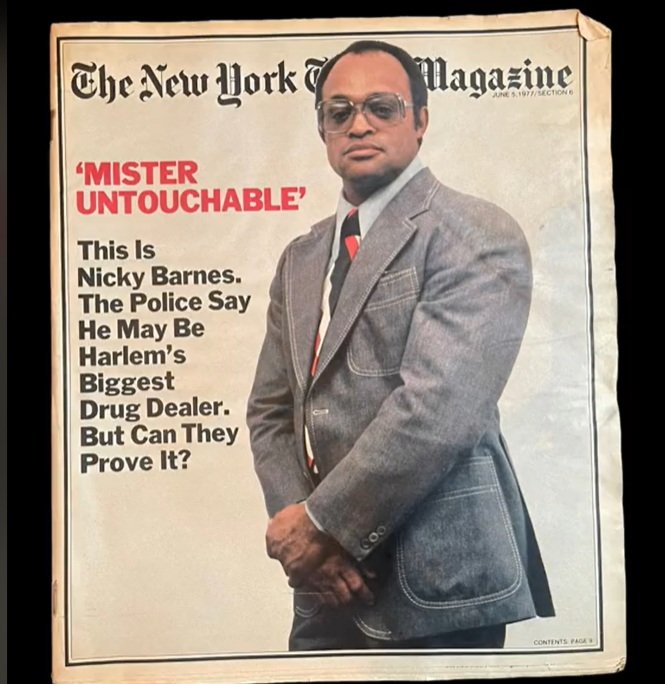

Hayden joined “the Council,” a seven-member committee made up of seven notable Harlem gangsters including Nicky Barnes, Guy Fisher, Thomas "Gaps" Forman, Frank James, Ishmael Muhammed and Wallace Rice.

Barnes was the subject of a feature-length 2008 documentary, Mr. Untouchable. The Council itself is the subject of an upcoming Netflix mini-series starring Will Smith titled “The Council.”

"This group is no more than just a bunch of guys with similar backgrounds who grew up in the same neighborhood," Hayden said in Mr. Untouchable. "People that are locked out, have to find some kind of innovative way to get in."

"In the process," he explained, "they become what I call 'sidewalk executives.'"

English, who interviewed Hayden about his time on the Council, said Hayden's decision to join the group was economic realism.

"That if this product was going to be in the marketplace," English summarized Hayden's thinking, "that there be a council to protect the community's interest in getting the profit from it. To create muscle in the underworld to get their right piece of the pie."

Hayden "was not to be trifled with," English added. "He was like a warrior." He "kept himself in top physical condition to always be ready for battle."

Joseph, the Black Panther-turned-college professor, first met Hayden in 1974. By 1975, he had a three-story building on Malcolm X Boulevard between 117th and 118th. His restaurant, Jagazy's, was on the first floor, "the second floor was a club, with a bar and dancefloor. The third floor was his office, dojo and sauna."

Hayden knew Joseph was trained in martial arts and wanted to work out with him. Joseph said he was happy to oblige because "Jazz was our comrade from prison." When they saw each other, they greeted each other with a "hug and kiss" the "way warriors hug when they were going off to or coming back from battle."

After a workout, they would shower, sit and talk or eat and drink, sometimes for hours.

Hayden "was all of these things at once," Joseph recalled. "We talked about rebuilding Harlem. Even then. We talked about Revolutionary ideology. He was the gangster. The entrepreneur. He also understood the evil of police brutality and Capitalism. He was all of that at once."

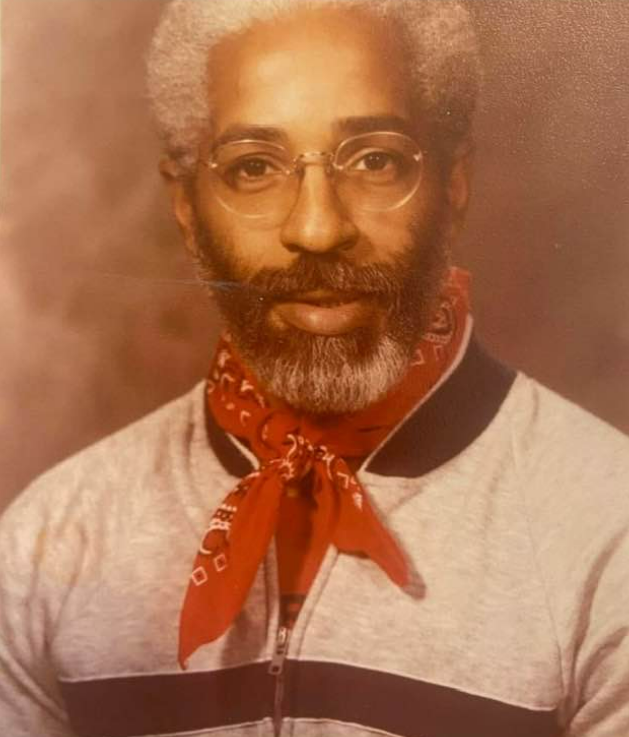

(1) & (2)Hayden & (3) Barnes Photo credit: Hayden via Facebook, Barnes screenshot.

The Council's downfall was triggered by Barnes' willing appearance in a June 5, 1977 New York Times Magazine cover article that called him “Mr. Untouchable.” The article prompted then-President Jimmy Carter to instruct his Attorney General, Griffen Bell, to reach out and “touch” the criminal kingpin to the fullest extent federal law would allow.

Federal prosecutors bought federal charges against the Council. They alleged it was the largest Black-controlled illegal drug distribution operation in America, that it sold more than $200 million in contraband narcotics per year between Jan. 1974 and Mar. 1977, that Barnes was its leader and Hayden its second-in-command.

Barnes, Hayden and six other members of the group were all convicted, after a two-month long trial, of conspiracy to distribute heroin and cocaine on December 2, 1977, court records show. Barnes was also convicted of being the boss of the group, which earned him a life sentence—later reduced after he became a federal informant.

Hayden and the Council’s main enforcer, boxer Leonard "Petey" Rollack, got 15 years, each. Three others got 30 years, one got eight, one got six.

When they were sentenced on January 23, 1978, the New York Daily News reported all but one of the once-feared group "appeared somber."

The exception was Hayden, described as the No. 2 man in the Barnes organization, who most of the time grinned from ear to ear and waved to his most elegantly attired courtroom well wishers. He declared to the judge, 'I'm not guilty of anything ... there's no justice.'

Hayden's real-life words were shoplifted by Hollywood script writers for the iconic 1991 American crime drama, “New Jack City.”

"I'm not guilty. You're the one who's guilty," the movie's fictional drug dealing kingpin, Nino Brown, famously says from the witness stand during his trial.

Hayden was paroled from federal prison after a decade, at least part of which was spent in Lewisburg. He stabbed a man to death during a traffic dispute in 1987. He said it was self-defense (maybe by Lewisburg’s expansive standard it was) but was convicted of what New York law calls manslaughter. He was sentenced to 10 to 20 years and did 12. First he earned a bachelor's degree then a master's degree at Sing Sing.

New York Daily News, page 5, Jan. 4, 1978.

I met Jazz in 1995, at New York's medium-security Woodbourne Correctional Facility. He had a small office in the law library and was in there pounding away like the Hemmingway of jailhouse lawyers at a big, brown IBM Selectric III typewriter when I first walked in. The falling keys flew like bullets and made a sound a lot like music to my own jailhouse lawyer ears.

I liked Jazz because I saw he was a finely-calibrated mix of tough, smart, observant and humble. A unique and potent hybrid of political consciousness, intellectual power, street knowledge and force. He liked me because I was suing Pres. Bill Clinton's administration in federal court for eliminating funding for prison college programs by enacting the then-Sen. Joe Biden-sponsored Crime Bill in 1994—which fueled the expansion of mass-incarceration.

Inside the law library at Woodbourne, Jazz liked to hold court.

Before Alexander published The New Jim Crow in 2010 and popularized the concept of “mass incarceration," there was Jazz railing against what he then called "neo-slavery." Back then Jazz described neo-slavery as the mass imprisonment of Black Americans and the systemic, court-sanctioned stripping of their civil rights—like Alexander would a decade-and-a-half later in The New Jim Crow.

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden attending college in prison in the early 1990s. The Crime Bill eliminated funding for prison college programs in 1996. Photo credit: via Facebook.

At Woodbourne in 1996, Jazz was closely following a federal lawsuit a group of prisoners at another New York prison had brought alleging they were being illegally denied the right to vote. The trial-level District Court dismissed the prisoners' suit, but a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed in Baker v. Pataki and ordered the case be sent back down to the District Court for trial.

But then a majority of all the judges on the appeals court decided to rehear the case en banc. 10 judges reheard the case, and split 5/5 down the middle. The District Court's dismissal was affirmed by default on May 30. Jazz showed me the decision in the New York Law Journal, a daily legal newspaper the prison law library received. He asked me what I thought.

By then I'd gotten pretty good at filing federal lawsuits and I knew what that split decision meant. It meant it was an open door. Legally it meant it had little power as precedent. Practically it mean another suit on the same grounds could be filed and a court would not be legally required to dismiss it. A judge would have to consider it fresh.

I got transferred to another prison a few months later.

Jazz formulated that federal civil rights lawsuit and mailed it to the court on September 13, 2000. He chose September 13 "in honor of those that died in Attica while demanding to be treated as human beings and not as chattel slaves." The "lawsuit was the product of social and historical research, by prisoners." The court determined it wasn’t frivolous, granted Jazz’s request to waive the filing fee because he couldn’t afford it and assigned it to a judge that December to be decided in due course.

The lawsuit would ultimately lead to Hayden's ideas and work reaching a national audience beyond prison walls.

Like he inspired so many others, Jazz inspired me at Woodbourne.

I applied to prison officials for permission to form a prisoners' rights organization, run by actual prisoners. Prison officials denied my application. I sued in Federal court under the First Amendment. After a six-year legal battle, I won.

Jazz and I were nearing the end of our sentences by then. I was released in 2003 then graduated NYU and went to work as a journalist in 2006.

A New York Law Journal front-page report from July 6, 2001, documenting the author’s prisoners’ rights victory, inspired by Joseph “Jazz” Hayden. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Hayden was home in time for Christmas 2001 and continued working as activist reformer. He wrote an Op-Ed in support of his voting rights lawsuit that was published in newspapers across the Nation, from the Morning Sentinel in Waterville, Maine to the Brattleboro Reformer in Vermont all the way to the Tyler Morning Telegraph in Texas and even the Fresno Bee in California.

The lawsuit, however, failed when the Second Circuit essentially invented reasons to ignore the plain meaning of the Voting Rights Act in its 2006 decision, Hayden v. Pataki.

While Hayden lost the courtroom battle to get parolees and prisoners the right to vote, he eventually won much of that war.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 181 restoring the right to vote to parolees on April 18, 2018. Then he signed a bill into law permanently restoring parolees' right to vote in 2021.

"Since 2018, a growing number of states have changed their laws—either through constitutional amendment, legislation, or executive action—to allow more Americans with past convictions to vote, the Brennan Center for Justice reports. "Other states are considering similar reforms."

After Hayden filed the lawsuit, lawyers from the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund took the case. One of them, now LDF President and Director-Counsel Janai Nelson, issued a statement on Thursday mourning his loss and recognizing him as a "trailblazing advocate for voting rights of incarcerated people."

“Mr. Jazz Hayden was an extraordinary activist and brilliant strategist who, in the name of justice, worked to redefine what it means to be an incarcerated citizen in a democracy.”

"He will be sorely missed," Nelson added. His "legacy remembered for generations to come."

Janai Nelson, President & Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (l) with (c) Joseph “Jazz” Hayden; Hayden in Harlem. Photo credits: via Facebook.

Steven "Humble" Mangual was serving time for manslaughter and assault when he, like me, met Jazz at Woodbourne. Today he is the national Justice Advocate Coordinator for Latino Justice. He works to convince lawmakers "to transform the criminal legal system."

"I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for Jazz," Mangual said. "It was taboo to say you had a felony back then. You were a Leper for real."

Hayden and another Black Panther veteran-turned-incarcerated scholar-and-activist, Eddie Ellis, "all them going back to the Green Haven Think Tank, they were the ones who made it OK to say you had a felony and were looking for work," Mangual explained

"I was just following the lead of Jazz and them," he added. "I never imagined I could lead a national criminal justice group."

Hayden’s impact was being "instrumental in expanding what we understand to be the civil rights movement. It includes the 2.3 million-plus people that are confined."

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden broadcasting the radio show “On the Count” with Steven “Humble” Mangual at WBAI radio in New York City. Photo credit: courtesy of Steven Mangual.

Glenn E. Martin, another of the many formerly-incarcerated folk-turned-reform advocates mentored by Hayden, said Ellis was like the Godfather or Dr. Martin Luther King of the prisoner-turned-activist breed of reformers.

"Hayden," he clarified, "was like Malcolm X. He was always there as Ellis's enforcer." He "was the litmus test. If you were full of shit he would know it." He "pulled no punches. He always spoke truth to power."

"Jazz," Martin added, pointedly, "was able to carry a truth most advocates today cannot: people can go in and out of bad and still be good."

Five Mualimm-ak is the Founder and Director of the Incarcerated Nation Network, which works against mass-incarceration. He remembered Hayden had a gift to "just reach people." He "made street hustlers into organizers." He "made it cool for gangsters to be activists."

Mualimm-ak knows what he is talking about because, he says, "I was a gangster, straight-up." Now "I'm giving talks at the UN, Columbia, UCLA. I'm teaching at the New School."

Hayden connected academia with the street, and vice-versa.

"I got out of prison on a Tuesday in 2010 and on Thursday I was on a stage with Angela Davis, Marc Lamont Hill, Pam Africa and Jazz to launch the Attica is All of Us foundation," Mualimm-ak recalled, with glee.

"To rise people up from prison out into the world to become leaders. That's what Jazz did."

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden with Five Mualimm-ak. Photo credit: courtesy Five Mualimm-ak.

Hayden also helped Michelle Alexander see the criminal justice system the same way he saw it while she was writing The New Jim Crow.

"Her book is a compilation of Jazz's anecdotes," said Martin, who helped organize the Close Rikers movement in New York City and today creates affordable housing. “It was Jazz's message. She was the messenger."

Mualimm-ak agreed. "That's Jazz's book," he said. "Jazz put that book together with Michelle. It was based on Jazz."

Mangual, who also worked with Hayden during this time, remembered “seeing him working with Michelle Alexander. She would contact him. He was like a consultant. He was a point person."

"He cared more about getting the message out, than getting credit for the message, " is how English—who interviewed Hayden multiple times— diplomatically phrased it. “That's the kind of guy he was."

When The New Jim Crow was published January 1, 2010, Hayden "just got behind" it, English remembered. He co-founded a National Campaign to End the New Jim Crow with the Americans' Friends Service Committee based out of Harlem's Riverside Church. The campaign was organized around study groups based on the book. The book became a bestseller.

He "did all he could to promote that book and bring it to the attention of everyone," English said. He never expressed any "resentment or any feeling that he'd been ripped off."

Hayden "was the only reason Cornel West and Angela Davis did new forwards for" Alexander’s book, Mualimm-ak said. The new forwards drove more sales, he added, bringing more converts to the cause.

Multiple attempts to contact Alexander for comment were not successful.

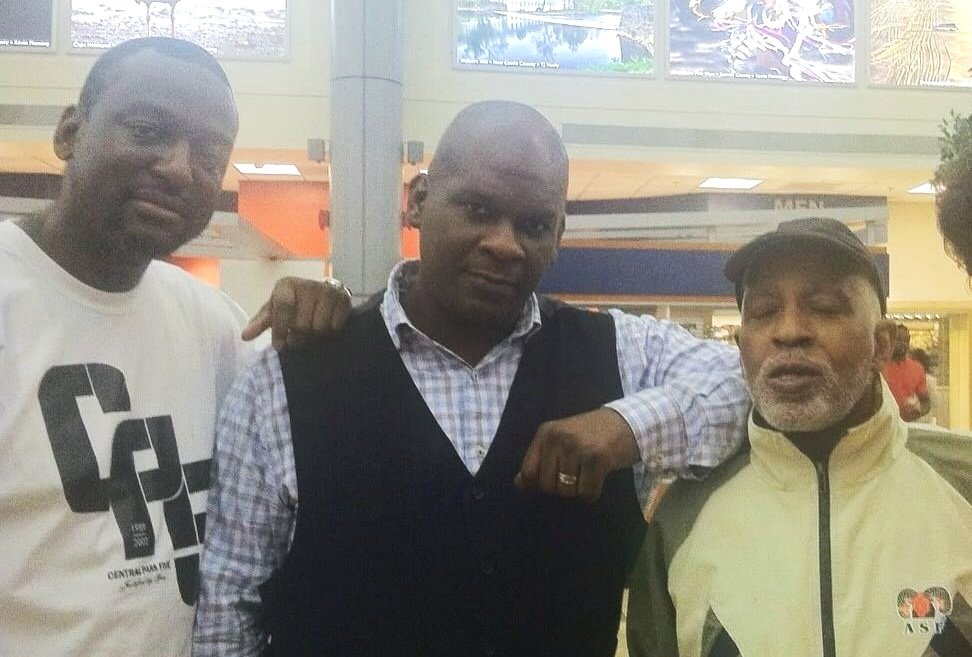

New York City Councilmember Dr. Yusef Salaam (l) with (c) Five Mualimm-ak and (r) Joseph “Jazz Hayden; and Hayden. Photo credit: via Facebook.

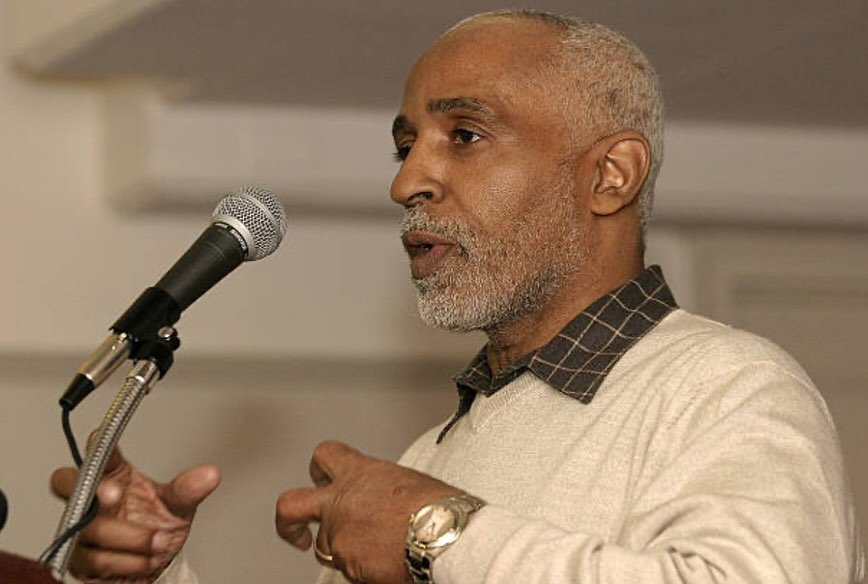

Hayden started publishing an Internet-based news blog in 2009. He named it All Things Harlem and described it as "a miniature CNN for Harlem." The New York Times covered its launch, A Newsroom to Cover the Disenfranchised Voices of Harlem. Hayden listened to those voices and heard them constantly complaining about the NYPD's aggressive and allegedly unconstitutional mass stop-and-frisk practices.

Joseph, Hayden's Black Panther friend from the 1970s who by then was chairman of Columbia University’s graduate film program, said Hayden made "it his mission to organize around police repression."

This time, instead of a lawsuit filed in a court, the weapon Hayden chose to fight stop-and-frisk was a camera.

This was before Smartphones were ubiquitous. The by-then almost 70-year-old Hayden went out with a video camera and filmed police stopping and frisking residents on the street. He spent the next four years, the Village Voice said in 2012, "irritating police officers by videotaping them as they stop and frisk people in Harlem in a program he calls 'Copwatch.'”

NYPD officers stopped, searched the Jeep Hayden was driving and arrested him in December 2011. They alleged he illegally possessed a knife and miniature, ceremonial baseball bat

"The police more than anything else they fear the camera," Hayden asserted, after a court appearance outside Manhattan Criminal Courts. "It's not the gun that they fear, it's the camera that they fear. That’s why I’m here.”

Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance's office essentially made Hayden plead guilty, but agreed to dismiss the charge if he stayed out of trouble for a year and performed five days of community service.

English, the crime journalist, said by then Hayden was beginning to acknowledge the evil he'd done in the world. He "was somewhat grappling with the morality of it all."

"He did feel some guilt," English believes, "and he was trying to make amends for that through his activism."

U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled the NYPD's stop-and-frisk program violated the Constitution in a bomb-like 2013 decision that banned it as it was then being practiced. Hayden won again.

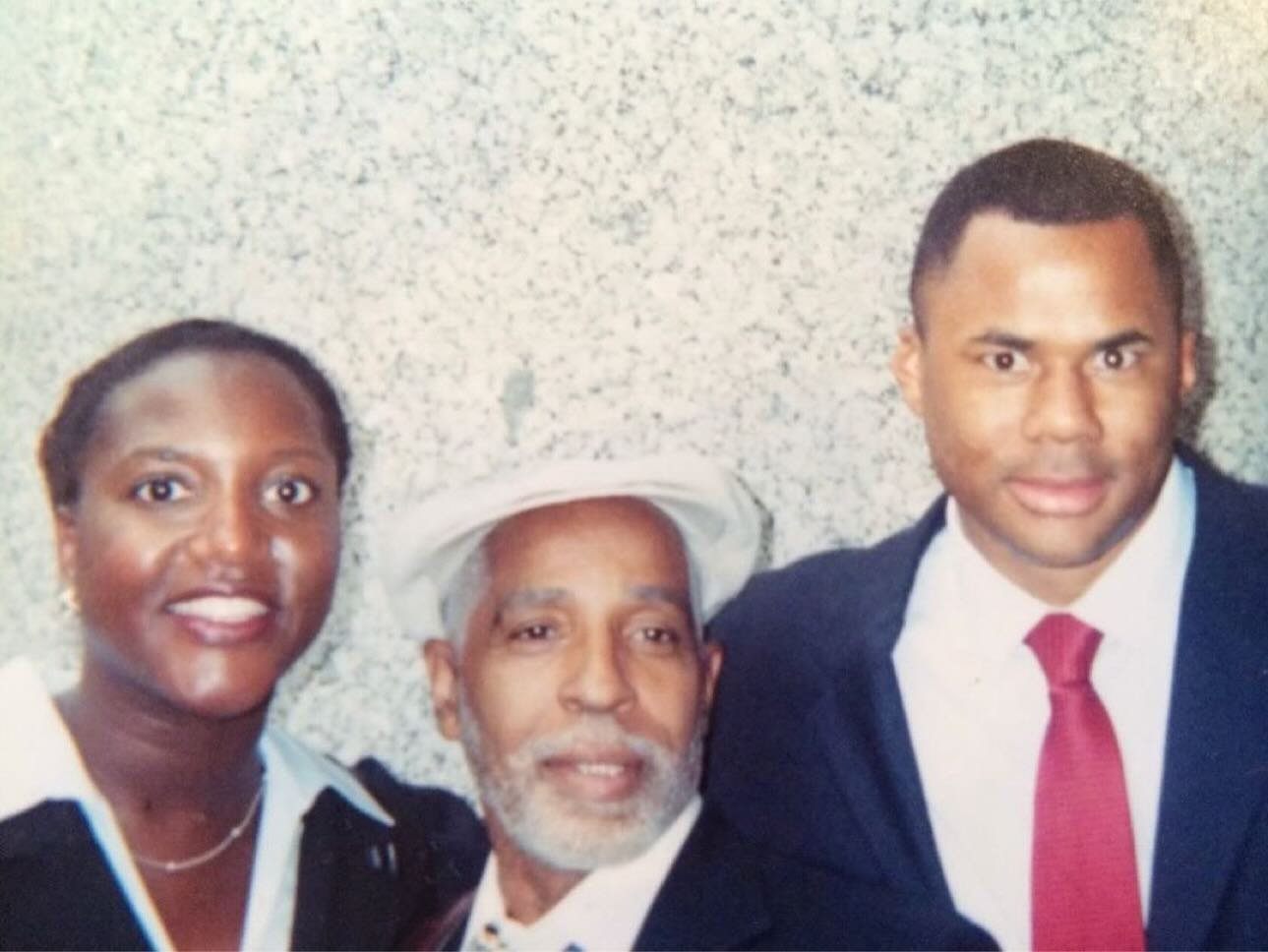

Photo credit: courtesy of family of Joseph “Jazz” Hayden.

The trumpet-playing child hustler gave himself the last word.

"We're saying dismantle this prison industrial complex," he finally concludes in a memorial video posted to X by the NAACP. "I'm committed to struggle against this system. I want that to be my legacy."

Joseph "Jazz" Hayden is survived by one sister, seven children, 12 grand-children and two great-grandchildren. His wife, Sylvia Freeman, predeceased him. Wake and funeral are Saturday January 13, 2024 at 1:00pm at the Boyko Funeral Home in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

THE FREE LANCE NEEDS YOUR DONATIONS TO SURVIVE. DONATE HERE.